Table of contents

The past and present of the textile industry in NRW will be the topic of a series of blog entries on our website.

We’d like present current exhibits and companies on the topic of fashion and textiles and take a closer look at the history of the textile cities in the Rhine and Ruhr region. Let’s start with Krefeld, the location of our headquarters:

The textile industry in Krefeld – velvet and silk

Krefeld is also know as the “city of velvet and silk” because of its rich history in textiles. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the focus was primarily on the production of silk fabrics. If you walk through Krefeld’s city centre, you can see a statue in Ostwall of a silk weaver carrying a roll of cloth on his shoulder. He’s known in Krefeld as “Master Ponzelar”. The statue is an homage to the golden age of textiles and to the craft of weaving.

If you’d like to experience the history of textiles at its best, then there’s lots of opportunities to do so in Krefeld! The House of Silk Culture, the Krefeld Pavilion by Thomas Schütte and the German Textile Museum offers insight into the history of the local textile industry, which offers visitors a wonderful world in which they can immerse themselves.

The German Textile Museum is located in the Krefeld district of Linn, a part of town where you can still find a bit of old medieval flair. The current exhibit located there is worth a visit.

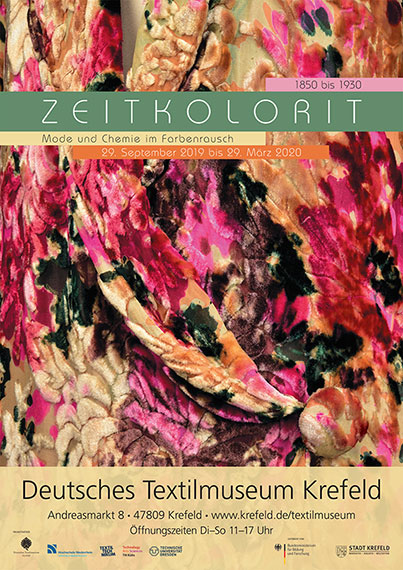

“A colourful journey back in time. Fashion and chemistry in a rapture of colour”

29 September 2019 to 29 March 2020

In the exhibit “A colourful journey back in time – Fashion and chemistry in a rapture of colour” at the German Textile Museum in Krefeld, Annette Paetz, or Schieck, together with her team, presents a breathtaking selection of colours, designs and fabrics – and gives us a little chemistry lesson in the process. At the focus of the exhibit is the evolution of fashion, particularly women’s fashion from the 1850s to the 1930s. Special attention is given to the vividness of the colours and their connection to the history of synthetic dyes, which were discovered by coincidence in 1865. From tar, which was nothing more than a by-product of coal processing, came the first synthetic dye: mauve, a slightly violet colourant.

A tour through the exhibit for the intercontact fashion translators

The fashion translators from intercontact took part in a professional tour through the exhibit, which was led by Mr Michaeli. The focal point of the exhibit was fashion and dying techniques throughout the years. Mr Michaeli talks about the first dying techniques with natural colourants and which raw materials belong to the natural colourants. The answer lies in a small bowl of chopped madder roots, displayed there for all the visitors to see. From this root, a red dye was produced. Lying a little further away, we see a bottle filled with ground scale insects. Even the dried up bodies of the cochineals create a red pigment.

The discovery of synthetic dyes represented a turning point for the textile industry. The discovery was pure coincidence. The well-known chemist William Perkin from Great Britain was searching in 1856 for a cure for the treatment of malaria. There was no medicine for malaria at the time. Instead, he developed a purple dye (mauve) from tar, a by-product of coal processing. Perkin’s discovery triggered an important development that accelerated advances within the chemical industry in Germany, the road to which had already been paved by the companies Bayer and BASF. Soon after, Germany would sky-rocket to its position as one of the leaders in the development of synthetic dyes.

The new dying process was less labour-intensive and fashion items were more affordable. The development of textile printing furthermore ensured that new clothing could be made more affordable to those from the less affluent strata of society. However, with the benefits that these new developments brought also came disadvantages. The dyes were not always lightfast, and some even turned out to be poisonous. Paris green, for example, proved to be a poisonous dye that caused health problems. At that time, there were no laws yet with respect to the protection of health and safety at the workplace.

We continue our tour and take one last look at some bottles of natural and synthetic indigo and kindly thank Mr Michaeli for the tour. The information he provided about fashion, chemistry and dyes proved to be both interesting and intelligible. The exhibit, with its selection of 50 dresses and numerous accessories from the collection of the German Textile Museum in Krefeld, was quite impressive.

Marian Verstraaten from intercontact makes an observation regarding the translation business:

“As a translator, you should always keep in the know about the subject material you’re translating. This also goes for the subject of textiles. Many of the techniques involved in the processing and treatment of textiles are quite abstract, not to mention the chemical processes involved. Take an indigo blue garment wash, for example – what exactly is this? The first thing that comes to mind for most people is jeans. But is what we think we know enough? A good translator knows what they’re talking about. They need to be passionate about their work. Of course, it’s also important to constantly stay informed about the subjects you specialise in. That’s what separates the wheat from the chaff.”

We believe that the connection between textiles, Krefeld and intercontact is somewhat more complex and that’s why we’d like to delve deeper. More on this in our next blog entry!

The exhibit at the German Textile Museum was organised by the Fachhochschule Niederrhein. The project partners are the German Textile Museum in Krefeld, the Rheydt Textile/Institute of technology, the TH Cologne and the TU Dresden.